AND WE WENT: 60 YEARS AFTER THE BATON ROUGE SWIM-IN

Curated by Jonell Logan

July 5 - 27, 2023

open to the public, free of charge (Tue-Sun, 12-6pm)

THE HISTORY OF The Baton Rouge Swim-In

by Melissa Eastin

Archivist & Head of Special Collections, East Baton Rouge Parish Library

“There was no such thing as recreation facilities in the early, late fifties and early sixties for blacks so I told my mother, I said, ‘One day I’m going to swim in that pool.’ And my mother says, ‘Maybe not you, but your children, maybe your children’s children or somebody might swim in that pool.’”

Pearl George, 1983

In the 1920’s the city of Baton Rouge began construction of a recreational facility on 165 acres of swamp on what was then the outskirts of town. City Park had everything; a nine-hole golf course, eight tennis courts, a playground, merry-go-round, a large lake for fishing, a club house and a swimming pool. At 20,000 square feet, the lagoon shaped pool with sloped edges allowed swimmers to walk into the water, similar to a natural beach. The only public swimming facility in Baton Rouge at the time, the City Park pool opened to the public on August 3, 1928, and like all public facilities in Baton Rouge, was for whites only.

Aerial view of City Park circa 1930

“Separate but Equal” was the rule of the nation at this time and despite paying equal taxes, Blacks in Baton Rouge were not provided the same types of recreational facilities as their white counterparts. With no other options, Black children often swam in the Mississippi River, creeks, and drainage ditches. One such ditch earned the name “Graveyard Creek” due to its close proximity to a cemetery. These waterways were dangerous, attracting snakes and rife with strong currents that sometimes proved fatal to these children.

Swimmers at Brooks Pool in 1953

In response to the need for safe recreational spaces for Black Baton Rougeans, Rev. Willie K. Brooks established the United Negro Recreation Association in 1945. By 1947, the UNRA gained enough funds from donors and the city to build a community pool. Opened in 1949, the park and pool quickly became a social hub of the Old South Baton Rouge neighborhood. The UNRA donated the Brooks Park Pool to BREC in 1953 and the organization took over the operation and maintenance of the facility. Even though the founding of Brooks Park Pool was viewed positively, members of the Black community were still marginalized by the segregation of BREC facilities. Activists argued that because Black people paid the same taxes as whites, they should be permitted use of the facilities maintained by those taxes.

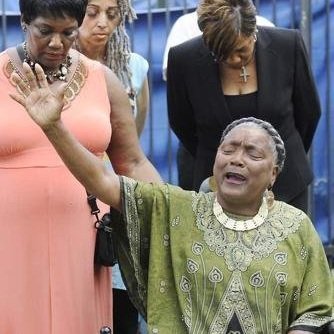

Betty Claiborne, who was officially pardoned by Gov. Kathleen Blanco in 2005

The first of several protests at the City Park Pool – what later came to be known as The Baton Rouge Swim-In - occurred on July 23, 1963, when a group of about 50 Black people led by Rev. Arthur Jelks (then president of the local NAACP chapter) approached the pool. The police were tipped off by an anonymous phone call and five officers as well as police chief Walter Wingate were at the pool when the protestors arrived. The group entered the clubhouse and proceeded to the pool area, but did not get in the water. There they were confronted by the manager, Gordon Clanton, and were asked to leave. Police met the group in front of the clubhouse where physical altercations occurred between officers and the protestors.

Pearl George, Sam Green, Betty Jean Wilson (Claiborne), James F. Williams, and Richard Thompson were all arrested and charged with disturbing the peace and simple battery. George’s eleven-year-old daughter, Debra, was also taken into custody, questioned without an adult present, and released. The adults were released on bond except Pearl George who said she preferred to remain in jail. The protesters were ultimately convicted, with Williams and Wilson receiving fines of $100 or 50 days in jail. George drew a six-month parish jail sentence plus a $250 fine or an additional six months in jail. Green and Thompson drew an additional $100 fine or 90 days in jail on a charge of resisting arrest and battery.

Civil rights attorney Johnnie A. Jones Sr.

Civil rights attorney Johnnie A. Jones Sr. first filed Lagarde v. Recreation and Parks Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge on November 17, 1953, in East Baton Rouge Parish. The suit challenged the legality of segregation in public recreational facilities in Baton Rouge. Ultimately refiled and ruled on by U.S. District Court on May 18, 1964, the ruling stated that there was, “There is no legal obligation or duty on the part of the City-Parish to provide or operate recreational facilities, but if they do, they cannot provide and maintain them on a racially segregated basis.”

BREC closed City Park and 9 other public pools in the area shortly after the resolution of the case, citing declining revenues and damage caused by an Alaskan earthquake. While other facilities eventually restarted operation in the following few years, City Park Pool never reopened. Left to stagnate, it was finally filled in 1990.

And We Went’s presenting partners would like to thank Melissa Eastin and the East Baton Rouge Parish Library (EBRPL) for their diligent research and assistance

additional resources

This exhibition is made possible by:

UPCOMING EVENTS

This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. This program is also funded under a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, the state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of either the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities. It is also supported by a grant from the Louisiana Division of the Arts, Office of Cultural Development, Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, in cooperation with the Louisiana State Arts Council, as administered by the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge.

To learn more about Baton Rouge Gallery and its exhibitions or programming, call 225.383.1470